This article first appeared in our Fall 2019 Magazine

By Loryn McGill, M.S., CCC-SLP

When Brandon stepped into my office a few weeks ago, he did not know the word "stuttering." Yet, surely in his own way, he did know it. It was the name of what caused him to struggle in conversations and to lose his breath; to add filler phrases in subconscious desperation, creating confusion for listeners when he talked. Other people could talk smooth and he talked bumpy. Previous speech therapy had attempted to teach him to “not stutter” and praised fluent speech.

When Brandon stepped into my office a few weeks ago, he did not know the word "stuttering." Yet, surely in his own way, he did know it. It was the name of what caused him to struggle in conversations and to lose his breath; to add filler phrases in subconscious desperation, creating confusion for listeners when he talked. Other people could talk smooth and he talked bumpy. Previous speech therapy had attempted to teach him to “not stutter” and praised fluent speech.

In his world, he was the only person like him.

As a Speech-Language Pathologist and Professor who exclusively works with people who stutter, I have seen what happens when we as professionals avoid talking about stuttering. We perform verbal dances and issue magic phrases to keep from using the word: ‘stuttering’. In so doing, we convey to children that what they are doing is bad. So bad that the mere use of the word ‘stuttering’ is taboo. The word becomes shame, pressuring the child to stop and reinforcing the great lengths many will go to in order to do so.

The struggle that Brandon exhibited in his speech was intense. Our first session was spent talking about stuttering and understanding everything that came with it. How it made his eyes look away, throat feel tight, and words feel scary. As he learned more that day about the word - "stuttering" - he found himself on his way to becoming an expert on his own stuttering.

For our second session Brandon came in wearing a Houston Astros hat. I pulled out a copy of the Stuttering Foundation newsletter and showed him the picture on the cover of MVP George Springer from the Houston Astros. The revelation for Brandon that a player on his favorite team stuttered was one of pure disbelief.  In fact, it turned out that Brandon was going to an Angels v. Astros game a few weeks later for his 6th birthday. I shared with Brandon and his mother all about the work that George Springer does as a spokesperson for SAY (Stuttering Association for the Young). I suggested to Brandon that he make a sign telling George that he, too, stuttered.

In fact, it turned out that Brandon was going to an Angels v. Astros game a few weeks later for his 6th birthday. I shared with Brandon and his mother all about the work that George Springer does as a spokesperson for SAY (Stuttering Association for the Young). I suggested to Brandon that he make a sign telling George that he, too, stuttered.

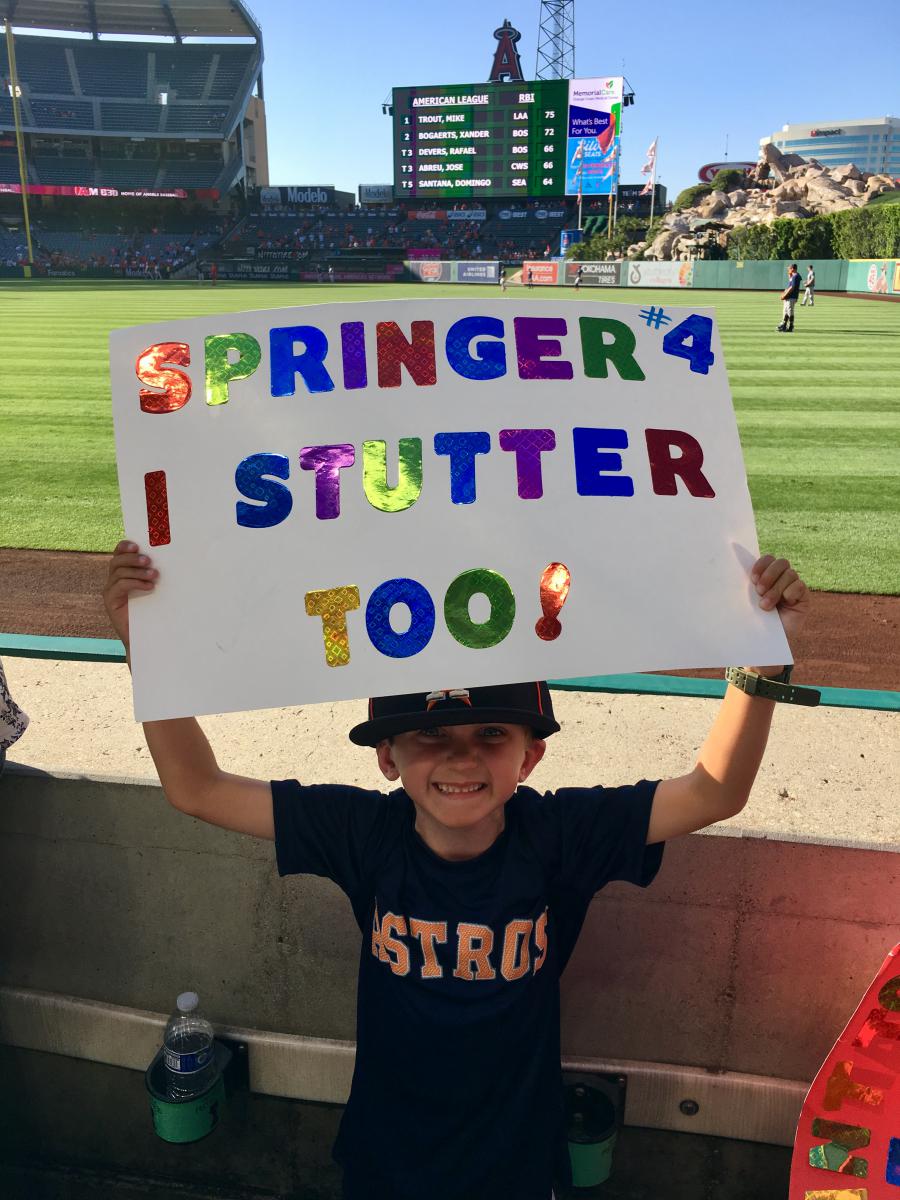

Brandon and his family went to two games that week. At the first game, Brandon and his family got to the stadium early for batting practice. George waved to a group of fans who were there close to the field and Brandon was certain that George was waving at him. He was hard to miss: Brandon could also be seen during the post-game show that night with his colorful sign, “Springer #4, I Stutter Too!”.

When Brandon went back for the second game that week, he got his chance. George saw Brandon with his poster and came over to talk to him. He told Brandon that it was okay to stutter, autographed a baseball card, ball, and took photos together. He then went back to the dugout and brought back a pair of his batting gloves. Brandon still wears them to sleep every night.

Brandon disclosed to everyone through his sign that he stuttered all because he saw someone that he admired and identified with, decreasing the stigma he felt about his own stuttering. He continues to grow in sharing his understanding of stuttering, now more confidently responding to questions from peers about his speech. He now knows he is not alone in his stuttering, and that it is okay to be open about his struggle ... just like George Springer.

Meeting George was surely a long shot on a summer night, but one that was only possible when we stayed true to our words.

From the Fall 2019 Magazine

Podcast

Podcast Sign Up

Sign Up Virtual Learning

Virtual Learning Online CEUs

Online CEUs Streaming Video Library

Streaming Video Library