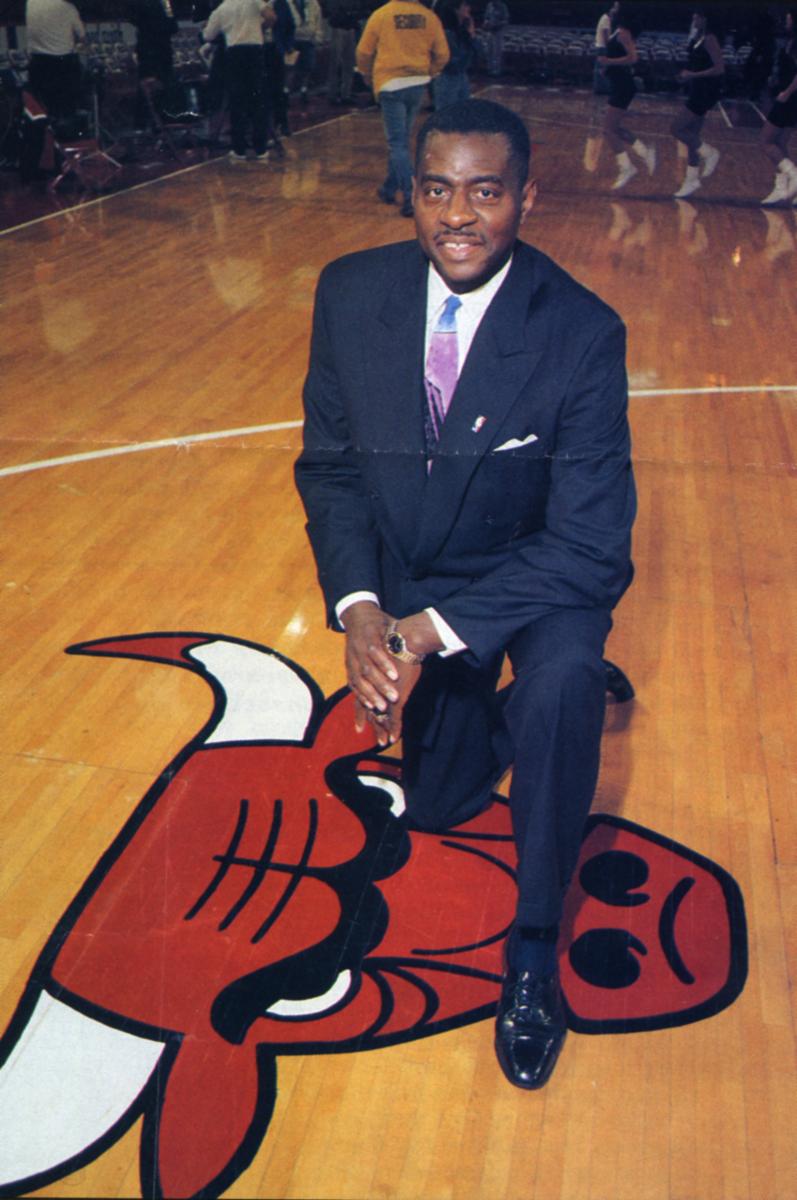

We are saddened to share news of the passing of Bob Love, NBA All-Star, friend of the Stuttering Foundation and inspiration to those who stutter.

We are saddened to share news of the passing of Bob Love, NBA All-Star, friend of the Stuttering Foundation and inspiration to those who stutter.

Love knew first-hand the experiences of someone who stutters. He overcame considerable frustrations and setbacks since his glory years with the Chicago Bulls.

The New York Times eloquently captured Bob’s struggles with stuttering in their recent article marking his death:

Love’s stuttering was so inhibiting that he seldom did interviews with reporters during his 11 seasons in the N.B.A., despite leading the Bulls in points per game or total points scored for seven straight seasons.

“The reporters had deadlines — they couldn’t hang around all night for me to spit something out,” Love told The New York Times in 2002.

Nicknamed Butterbean in high school because of his fondness for butter beans, Love even struggled to get words out in huddles during timeouts. A teammate, Norm Van Lier, often spoke up for him.

A back injury ended Love’s career in 1977, while he was with the Seattle SuperSonics. His marriage dissolved, leaving Love short on money — his highest season’s salary had been $105,000 — and out of work, largely because of his stuttering.

“All my life I dreamed and prayed to be able to communicate normally with people,” Love said in the 2002 Times article. “I would have given up everything else in my life to do it.”

“Bob was more than a great basketball star and community leader,” said Jane Fraser, president of the Stuttering Foundation. “He served as honorary spokesperson for Stuttering Awareness Week in the mid-1990s because of his courage in coping with his speech impediment.”

“I know how important it is to receive speech therapy at an early age,” Love said. “My grandmother Ella used to swat me in the mouth with a dishrag and say ‘Spit out those words, Robert Earl,’” he recalls. “That approach didn’t work very well, but it underscores the public’s misunderstanding of stuttering that is still prevalent,” said Love.

Difficulty in finding a job for those who stutter was nothing new to him. In the 1970s, he made the NBA All-Star Team three times. But he still stuttered, and there were fewer media interviews or endorsements than a player of his caliber would normally receive.

“After my retirement from the NBA, reaction by potential employers to my speaking difficulty turned the usually tough post-sports career adjustment into a living nightmare,” Love related. “I had a college degree, but personnel managers seldom call back someone who stutters on the telephone.”

By the end of 1984 —seven years after millions had watched him play NBA basketball — Love took the only job offered to him. He would wash dishes and bus tables for Nordstrom’s department store.

Yet it was here that Love’s story began a slow and difficult turn for the better. First, there was the corporate manager of Nordstrom’s, who offered to have his company pay for speech therapy. Enter speech pathologist Susan Hamilton Burleigh who would guide Love through countless hours of therapy in which he learned to manage his moments of stuttering and speak more fluently.

His time in therapy seemed to make a difference, as quoted in The New York Times article:

“His stuttering was severe — a lot of blank time, lack of eye contact,” Hamilton Burleigh said in a telephone interview. “He would tell me stories about being a Black player who stuttered and the work at Nordstrom, which were high on the list of shameful experiences.”

Love recorded himself in everyday interactions and analyzed his speech in sessions with Hamilton Burleigh. “He was super-motivated,” she said. “In one of our first sessions, he said, ‘I want to be a great public speaker.’ I said, ‘Well, OK.’ But after a while, he was going around Seattle giving speeches.”

Representing the Bulls, Love made speeches at schools, churches and community centers. He grew so confident that he knocked on doors all over Chicago’s 15th Ward in an unsuccessful run for the City Council in 2003.

Love was active with the Stuttering Foundation of America and maintained occasional contact with Hamilton Burleigh, who once attended a dinner at which Love was receiving an award. His speech that night was less than his fluid best.

“Here’s the deal on stuttering — there’s no cure, it’s just about managing it,” she said. “So I went back to talk to him after the speech and said, ‘We can always do a refresher.’”

Recalling his shame from their initial sessions, she was delighted by what he told her.

“Susan, no,” he said. “If people have problems with my stuttering, it’s their deal. It’s not keeping me anymore from doing anything I need to do.”

“Today my message to young people who stutter, and their parents, is direct: Don’t wait, like I did,” Love emphasized in 1994. “Speech therapy during childhood has the greatest chance of success.”

“Stuttering didn’t bench Bob Love,” said Fraser. “And he’s an All-Star in our book, too.”

Read more about Bob Love on our Famous People Who Stutter page.

Podcast

Podcast Sign Up

Sign Up Virtual Learning

Virtual Learning Online CEUs

Online CEUs Streaming Video Library

Streaming Video Library