By Jane Fry, MSc (Psych Couns)., Dip CT (Oxon) Michael Palin Centre (Fall 2009)

Cognitive therapy, or cognitive-behaviour therapy (CBT), is increasingly referred to in work with people who stutter. Jane Fry from the Michael Palin Centre, London, UK, discusses some of its' key theoretical and clinical principles.

Cognitive therapy, or cognitive-behaviour therapy (CBT), is increasingly referred to in work with people who stutter. Jane Fry from the Michael Palin Centre, London, UK, discusses some of its' key theoretical and clinical principles.

What is Cognitive Therapy?

Cognitive Therapy is a form of psychotherapy which was originally developed by Aaron Beck in the 1960's to understand and treat depression. Beck proposed that as human beings, we are constantly engaged in a process of filtering and interpreting information in order to make sense of the world and our experiences. While this is helpful because it makes the world more predictable, he argued that we all sometimes make errors, jump to conclusions or generally get things wrong. While it is human nature to make mistakes, Beck proposed that some people develop systematic, unhelpful biases in the way they interpret information, and patterns of negative or unhelpful thinking which help to explain their vulnerability to emotional problems.

Cognitive theory thus emphasises the role of cognitions (thoughts, assumptions and core beliefs) in explaining the way people feel. For example, when people feel anxious it is because they are predicting that an imminent situation will be threatening in some way. Furthermore, the level of anxiety will be higher the more a person views the feared event as being likely to happen, the more that is at stake should it happen, and the less the person views themselves as being able to cope.

Beck also proposed that thoughts, feelings, physiological and behavioural responses are linked. For example, when we get anxious a 'wired-in' response triggers physical feelings, such as 'butterflies' or an increased heart rate, and also a natural and instinctive behavioural response to something protective, such as avoiding the source of threat. Furthermore, in difficult situations people tend to respond in ways which inadvertently exacerbate or reinforce problems, creating a 'vicious circle'. Continuing with the example of anxiety, avoiding a feared situation might get an individual 'off the hook' but ultimately it stops them from finding out that things might have actually been OK, or not as bad as they feared, or indeed that they might have coped. The person loses the opportunity to build confidence and their fears associated with that situation are reinforced.

How might this relate to stuttering?

People who stutter often notice that when they feel apprehensive about speaking this is linked to negative thoughts or predictions about the situation. These tend to be about stuttering itself (i.e: 'I'll get stuck'; 'It'll go on forever'), how other people will react (i.e: 'they'll laugh at me, they'll ignore me') and how they will be viewed (i.e: 'they'll think less of me', 'they'll think there's something wrong with me'). They may then find that they approach the situation with more emotional and physical tension than they would otherwise have done, and that as a result they are indeed more likely to stutter. Alternatively they may cope by doing something protective, such as deciding not to speak, or choosing a safer word, which may offer a short term solution but not fit with how they want to cope with stuttering in the long term. Importantly, the dynamic of negative self-talk and use of unhelpful coping strategies can become a pattern which reinforces rather than diminishes anxiety about speaking. At a deeper and more complex level, individuals may develop an underpinning system of negative assumptions and beliefs which more generally influences how they experience the world.

What happens in therapy?

One of the first tasks is to help clients explore the links between their thoughts, feelings, physiological reactions and behavioural responses, to introduce the concept of the vicious circle and help them weigh up which of their typical ways of coping are helpful and which are less so.

Next, clients are encouraged to carry out 'experiments' which help them to test predictions and see how accurate they are. For example, a recent group of teenagers at the Michael Palin Centre spent a morning watching their therapists stuttering and noticing how members of the public reacted, a task which they threw themselves into wholeheartedly, ensuring that we all stuttered sufficiently to make the experiment valid.

Cognitive therapists use questions to help clients explore other perspectives, and reach their own conclusions, taking care to work collaboratively and avoid any sense of debate or instruction. Questions that we encourage clients to ask themselves include:

What is the evidence that supports my prediction?

Is there any evidence that what I'm thinking is not entirely accurate, or that something else could be true?

Is there another way of looking at things?

People are also helped to recognise when they are adopting an unhelpful pattern of thinking or 'thinking trap'. Our group of teenagers, and not a few of the therapists and students too, recognised some of the following:

All or nothing thinking:

This is where you look at things in absolute, black and white terms rather than considering a continuum of possibilities. Perceiving something to be a 'total failure' or 'rubbish' because it is not 100% perfect is an example of all or nothing thinking.

Catastrophising:

You expect that the worst will happen even when there is no evidence to suggest that it might. You don't consider other possible outcomes which might be just as, if not more likely.

Mind-reading:

You make assumptions about what other people are thinking or are going to think.

Over-generalisation:

You make a sweeping conclusion on the basis of one event, that goes far beyond the current situation.

Mental filter

You dwell on the negatives and magnify them or blow them out of proportion, while ignoring or minimising the positives.

Post mortem thinking

You go over in your mind all the things that went wrong and don't pay attention to the things you did well.

Importantly, in cognitive therapy there is recognition that adverse events do occur. At times people who stutter face very real social stigma and sometimes fears are justified. One of the real strengths of this approach is that it focuses on building coping strengths and problem-solving skills so that individuals are more flexible in their thinking and more emotionally resilient when things are less than ideal.

Research and the evidence base

There is not a great deal of research into the use of cognitive therapy with people who stutter yet, however several studies have discussed links between social anxiety and stuttering, lending weight to a theoretical argument for its' use. Fry, Botterill and Pring (2009) and Menzies, O'Brian, Onslow and Packman (2008) have recently referred to the use of cognitive therapy as a component of treatment for, respectively, teenagers and adults who stutter, and certainly at a clinical level it seems to have a good fit with clients' experience and therapy goals.

In summary

Cognitive Therapy is not concerned with teaching clients to 'think positively' or to be more 'rational'. It is concerned with helping people to understand the way in which their thinking affects them on a day-to-day basis, and to cope with difficulties more effectively by being more flexible in how they look at and respond to situations, developing more effective problem-solving skills, maximising the use of more helpful self-talk, and developing life-enhancing core beliefs. It provides a structure for therapists to explore their own negative thoughts, emotions and responses, and to understand parents' anxieties better.

At the Michael Palin Centre cognitive therapy may be integrated into work on fluency skills, desensitisation or general communication skills, or it may be delivered on its own for young adults and adults who want to focus more the psychological aspects of their experience. It is particularly important in our work with children, parents and young people where developing a robust and positive self-view is likely to protect against future difficulties.

Where to find out more

There are a number of self-help resources available which provide a good place to start, some of which are listed below.

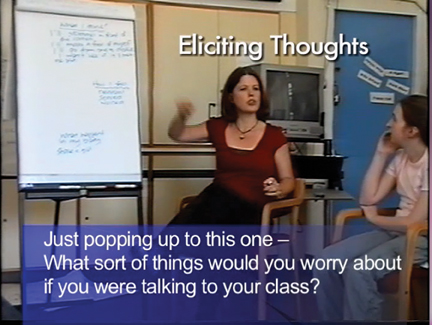

In addition, the Stuttering Foundation has recently released the DVD, Tools for Success, which provides a 'taster'to the core skills of CBT, presented by speech therapists from the Michael Palin Centre and based on a workshop held in Boston in 2008. (Photos shown in this article are found in the new DVD)

In the USA Christine Padesky is a high-profile clinician, writer and trainer at the Centre for Cognitive Therapy (www.padesky.com) who provides training and resources for mental health professionals.

References

Fry, J., Botterill, W., & Pring, T (2009). The effect of an intensive group therapy programme for young adults who stutter: A single subject study. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 11 (1): 12-19.

Menzies, G., O'Brien, S., Onslow, M., Packman, A., St Clare, T & Block, S. (2008). An experimental clinical trial of a cognitive-behaviour therapy package for chronic stuttering. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 51, 1451 -1464.

Self-help books

Butler, G. (1999) Overcoming Social Anxiety and Shyness. A self-help guide using Cognitive Behavioural Techniques. Robinson, London.

Butler, G. & Hope, T. (1995) Manage your Mind: The Mental Fitness Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Willetts, L., & Creswell, C. (2007). Overcoming your child's social anxiety and shyness: A self-help guide using cognitive-behavioural techniques. Robinson. London

Jane Fry, MSc (Psych Couns)., Dip CT (Oxon), is a specialist speech and language therapist at The Michael Palin Centre for Stammering Children, London U.K., www.stammeringcentre.org.?ÿ

New DVD: Tools for Success: A Cognitive Behavior Therapy Taster

Podcast

Podcast Sign Up

Sign Up Virtual Learning

Virtual Learning Online CEUs

Online CEUs Streaming Video Library

Streaming Video Library