An excerpt from chapter 6 of the book Advice to Those Who Stutter

By Joseph G. Sheehan, Ph.D.

If your experience as a stutterer is anything like mine, you’ve spent a good part of your life listening to suggestions, such as “relax, think what you have to say, have confidence, take a deep breath,” or even to “talk with pebbles in your mouth.” And by now, you’ve found that these things don’t help; if anything, they make you worse.

If your experience as a stutterer is anything like mine, you’ve spent a good part of your life listening to suggestions, such as “relax, think what you have to say, have confidence, take a deep breath,” or even to “talk with pebbles in your mouth.” And by now, you’ve found that these things don’t help; if anything, they make you worse.There’s a good reason why these legendary remedies fail, because they all mean suppressing your stuttering, covering up, doing something artificial. And the more you cover up and try to avoid stuttering, the more you will stutter.

Your stuttering is like an iceberg. The part above the surface, what people see and hear, is really the smaller part. By far the larger part is the part underneath—the shame, the fear, the guilt, all those other feelings that come to us when we try to speak a simple sentence and can’t.

Like me, you’ve probably tried to keep as much of that iceberg under the surface as possible. You’ve tried to cover up, to keep up a pretense as a fluent speaker, despite long blocks and pauses too painful for either you or your listener to ignore. You get tired of this phony role. Even when your crutches work you don’t feel very good about them. And when your tricks fail you feel even worse. Even so, you probably don’t realize how much your coverup and avoidance keep you in the vicious circle of stuttering.

In psychological and speech laboratories we’ve uncovered evidence that stuttering is a conflict, a special kind of conflict between going forward and holding back—an “approach-avoidance” conflict. You want to express yourself but are torn by a competing urge to hold back, because of fear. For you as for other stutterers, this fear has many sources and levels. The most immediate and pressing fear is of stuttering itself and is probably secondary to whatever caused you to stutter in the first place.

Your fear of stuttering is based largely on your shame and hatred of it. The fear is also based on playing the phony role, pretending your stuttering doesn’t exist. You can do something about this fear, if you have the courage. You can be open about your stuttering, above the surface. You can learn to go ahead and speak anyway, to go forward in the face of fear. In short, you can be yourself. Then you’ll lose the insecurity that always comes from posing. You’ll reduce that part of the iceberg beneath the surface. And this is the part that has to go first. Just being yourself, being open about your stuttering, will give you a lot of relief from tension.

Here are two principles which you can use to your advantage, once you understand them: they are (1) your stuttering doesn’t hurt you; (2) your fluency doesn’t do you any good. There’s nothing to be ashamed of when you stutter and there’s nothing to be proud of when you are fluent.

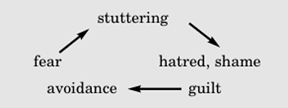

Most stutterers wince with each block, experiencing it as a failure, a defect. For this reason they struggle hard not to stutter and therefore stutter all the more. They get themselves into a vicious circle which can be diagrammed as follows:

Stuttering is a lonesome kind of experience. Possibly you haven’t seen too many stutterers and those you have seen you have avoided like the plague. Just as there may be people who know you or have seen you or even heard you who don’t realize that there’s anything wrong with your speech, so those who have a speech handicap similar to yours keep it concealed. For this reason few realize that almost one percent of the population stutter, that there are more than three million stutterers in the United States today. That many famous people from history have had essentially the same problem, including Moses, Demosthenes, Charles Lamb, Charles Darwin, and Charles I of England. More recently, George VI of England, Somerset Maugham, Marilyn Monroe, and the T. V. personalities, Garry Moore and Jack Paar have been stutterers at some time in their lives. In your speech problem you may not be as unique or as much alone as you had thought!

Each adult stutterer has his individual style made up usually of tricks or crutches which are conditioned to the fear and have become automatic. Yet they all suffer from basically the same disorder, whether they choose to call it stammering, a speech impediment, or something else. How you stutter is terribly important. You don’t have a choice as to whether you stutter, but you do have a choice as to how you stutter. Many stutterers have learned as I have learned, that it is possible to stutter easily and with little struggle and tension. The most important key in learning how to do this is openness: getting more of the iceberg above the surface, being yourself, not struggling and fighting against each block and looking your listener calmly in the eye, never giving up in a speech attempt once started, never avoiding words or ducking out of situations, taking the initiative in speaking even when doing a lot of stuttering. All these are fundamental in any successful recovery from stuttering.

You can stutter your way out of this problem. As long as you greet each stuttering block with shame and hatred and guilt, you will feel fear and avoidance toward speaking. This fear and avoidance and guilt will lead to still more stuttering, and so on. Most older therapies failed to break up the vicious triangle because they sought to prevent or eliminate the occurrence of stuttering which is the result of the fear. You can do better by reducing your shame and guilt and hatred of stuttering which are the immediate causes of the fear. Because stuttering can be maintained in this vicious triangle basis, there are many adults who could help themselves to speak with much less struggle if they would accept their stuttering, remain open about it, and do what they could to decrease their hatred of it.

Some individuals, given a start in the right direction, can make substantial headway by themselves. Others need more extensive and formal speech therapy.

Because you stutter, it doesn’t mean you are any more maladjusted than the next person. Systematic evaluation of objective research using modern methods of personality study show no typical personality pattern for stutterers, and no consistent differences between those who stutter and those who don’t. Maybe a little fortification with that knowledge will help you to accept yourself as a stutterer and feel more comfortable and be open about it.

If you are like most of the 3 million stutterers in this country, clinical treatment will not be available to you. Whatever you do you’ll have to do pretty much on your own with what ideas and sources you can use. It isn’t a question of whether self-treatment is desirable. Clinic treatment in most instances will enable you to make more systematic progress. This is particularly true if you are among those stutterers who, along with people who don’t stutter, have personality and emotional problems. Every stutterer does try to treat his own case in a sense anyway. He has to have a modus operandi, a way of handling things, a way of going about the task of talking.

I have tried to set down some basic ideas which are sounder and more workable than the notions that most stutterers are given about their problem.

You might go about it this way. Next time you go into a store or answer the telephone, see how much you can go ahead in the face of fear. See if you can accept the stuttering blocks you will have more calmly so that your listener can do the same, and in all other situations see if you can begin to accept openly the role of someone who will for a time stutter and have fears and blocks in his speech. But show everyone that you don’t intend to let your stuttering keep you from taking part in life. Express yourself in every way possible and practical. Don’t let your stuttering get between you and the other person. See if you can get to the point where you have as little urge for avoidance and concealment in important situations as you would when you speak alone. And when you do stutter—and you will—be matter of fact about it. Don’t waste your time and frustrate yourself by trying to speak with perfect fluency. If you’ve come into adult life as a stutterer, the chances are that you’ll always be a stutterer, in a sense. But you don’t have to be the kind of stutterer that you are—you can be a mild one without much handicap.

Age is not too important a factor, but emotional maturity is. One of our most successful recoveries on record is that of a 78-year-old retired bandmaster who resolved that before he died he would conquer his handicap. He did.

In summary, see how much of that iceberg you can bring up above the surface. When you get to the point where you’re concealing nothing from your listener, you won’t have much handicap left. You can stutter your way out of this problem, if you do it courageously and openly.

Podcast

Podcast Sign Up

Sign Up Virtual Learning

Virtual Learning Online CEUs

Online CEUs Streaming Video Library

Streaming Video Library