Two giants of publishing and media in the twentieth century dealt with stuttering all throughout their lives. A complete examination of the pioneering careers of each one is not possible in one article as their stuttering is the focus. Henry Luce and Walter Annenberg were not only highly successful publishing magnates, but also were among the very most influential Americans of their generation.

Two giants of publishing and media in the twentieth century dealt with stuttering all throughout their lives. A complete examination of the pioneering careers of each one is not possible in one article as their stuttering is the focus. Henry Luce and Walter Annenberg were not only highly successful publishing magnates, but also were among the very most influential Americans of their generation.

Henry Robinson Luce (1898–1967) was famous for being labelled “the most influential private citizen in the America of his day.” It was at the Hotchkiss School in Connecticut where he met lifelong business partner Briton Hadden, who served as editor-in-chief of the school newspaper while Luce was managing editor. The pair went on to Yale where Hadden was chairman of The Yale Daily News while Luce served as managing editor. Both worked at The Baltimore News for a year after graduating from Yale in 1920, and then they hatched their plan to form Time, Inc. and start Time magazine, which debuted with the March 3, 1923, issue. They would acquire and relaunch Life magazine, in addition to starting Fortune. House & Home and Sports Illustrated would follow in 1952 and 1954. Their empire also dominated the news reels shown in theatres across the U.S. Henry Luce was summoned for advice by various presidents.

In his 1991 book Henry & Clare: An Intimate Portrait of the Luces, author Ralph G. Martin puts forth that in 1905 at age seven Henry Luce underwent a difficult tonsillectomy of which the anesthesia wore off during the operation, causing great pain. Afterwards his stuttering started and his parents always blamed the operation. Spending his first 12 years in China on account of his father being a Presbyterian missionary, the young Luce attended a British school in China where his stuttering was mocked and set him apart from his classmates. It was at this school that the young American first made an effort to address his stuttering. Martin wrote, “Determined to overcome his stuttering, Harry helped start a debating society. He would not sit there and suffer his embarrassment, but would cope with it and conquer it. He was like an actor with stage fright, pushing himself before an audience. When troubled by his stutter, he would cock his head to one side and wag his head.”

At age 14 in 1912, Luce’s parents sent him to a boarding school in England in which the headmaster himself was a speech correctionist who had a reputation for helping boys overcome their stuttering. Martin wrote in his book about Luce’s year at the school, “Therapists tried to abort stuttering with a short, silent breath before each sentence. The breaths presumably relaxed the vocal chords enough to allow the person to speak fluently. Most therapists regarded the physical therapy as only part of the treatment. After five months, Harry felt helped, but not enough. His stammering hadn’t stopped. His own intense willpower and practice helped him much more in later years, but for the rest of his life, he stuttered when he got overly excited.”

While a student at Yale, Luce won the university’s top public speaking prize. In his 2010 book The Publisher: Henry Luce and His American Century, author Alan Brinkley wrote, “…he won the college’s most distinguished public speaking prize, the DeForest oratical contest- an especially rewarding feat for a young man who had worked for years to conquer his childhood stammer.” However, throughout his storied career Luce’s stuttering would reappear. Brinkley wrote of Luce’s 1966 interview with Eric Goldman, “He rambled in conversation, often stopping in midsentence and starting over again, circling around questions before actually answering them, sometimes speaking so fast that he seemed to be trying to outrace the stammer that had troubled him in childhood and occasionally revived in moments of stress.”

A passage in Martin’s book states that Luce’s colleague Andrew Heiskell noticed that the more Luce slept, the less he stuttered. “When I first knew him, he still stuttered,” Heiskell said. “Sometimes when he made speeches it was agony when he got stuck on something. But then the stuttering disappeared. The self-confidence was there.”

Henry Luce also addressed his stuttering in a most unconventional manner. All biographies on Luce state the well-known fact he and his wife, Clare Booth Luce, regularly took LSD in the 1950s. Before the 1960s era of Dr. Timothy Leary, LSD was unregulated. Oscar Janiger, a Los Angeles psychiatrist, was a pioneer with LSD who prescribed the drug to many A-list actors, such as Cary Grant and his wife actress Betsy Drake. An August 2010 article in Vanity Fair titled “Cary in the Sky with Diamonds” states that Mrs. Luce was the instigator in the couple’s experimentation with LSD.

“Another early experimenter was Clare Booth Luce, the playwright and former American ambassador to Italy, who in turn encouraged her husband, Time publisher Henry Luce, to try LSD. He was impressed and several very positive articles about the drug’s potential ran in his magazine in the late 50s and early 60s, praising Sandoz’ ‘spotless’ laboratories, ‘meticulous’ scientists and LSD itself as ‘an invaluable weapon for psychiatrists.’” Betsy Drake, a person who stuttered who used acting as a tool for fluency and Henry Luce noticed how LSD brought them a sense of fluency.

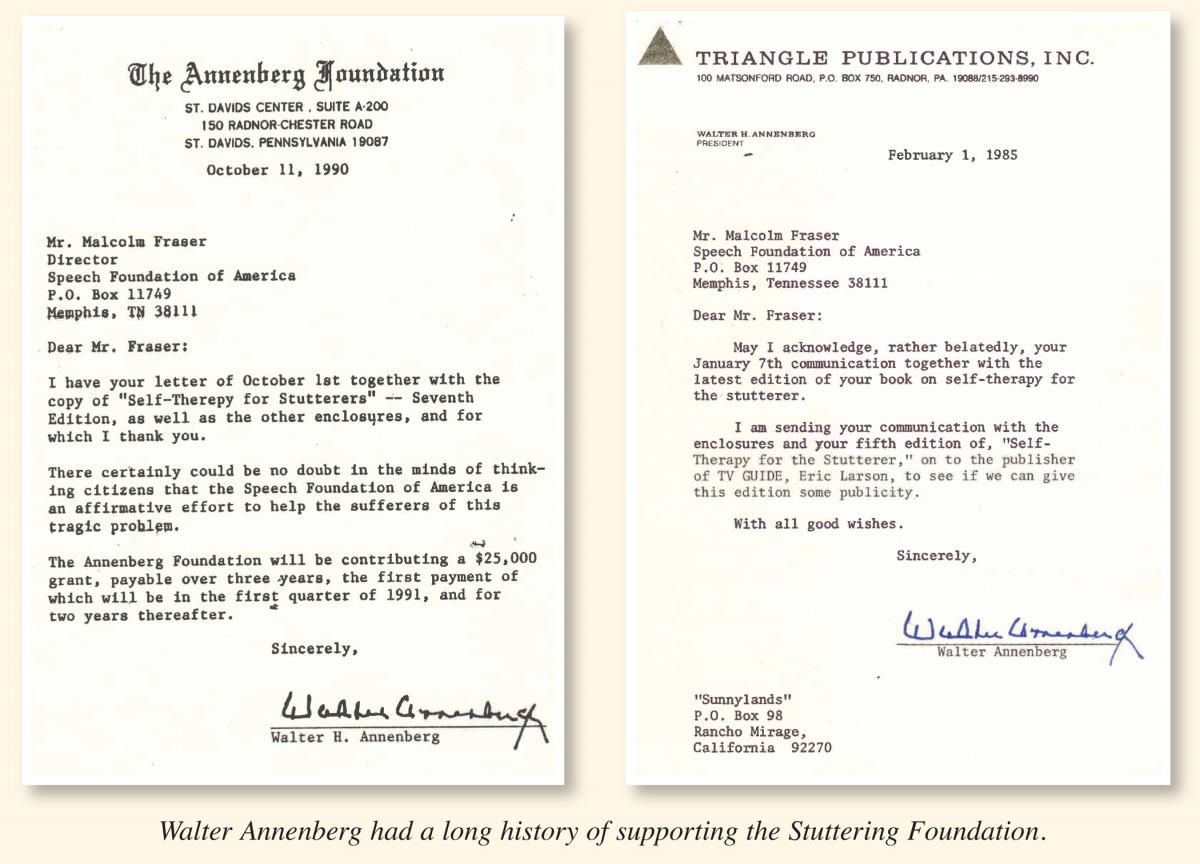

Walter Annenberg (1908-2002) was a publishing magnate in addition to being a philanthropist and a diplomat. Inheriting the Philadelphia Inquirer from his father, he built a publishing empire by creating magazines such as TV Guide and Seventeen in addition to accumulating many radio and television stations. He also served as the U.S. Ambassador to the United Kingdom from 1969-1974. His famous estate in Rancho Mirage, CA hosted countless functions with the top names in entertainment, politics, business, and royalty.

Walter Annenberg (1908-2002) was a publishing magnate in addition to being a philanthropist and a diplomat. Inheriting the Philadelphia Inquirer from his father, he built a publishing empire by creating magazines such as TV Guide and Seventeen in addition to accumulating many radio and television stations. He also served as the U.S. Ambassador to the United Kingdom from 1969-1974. His famous estate in Rancho Mirage, CA hosted countless functions with the top names in entertainment, politics, business, and royalty.

Annenberg’s Oct. 2, 2002, obituary in the New York Times stated that he struggled with stuttering throughout his life. In a 1982 book by John Cooney, the author writes, “By 1968, it is impossible to equate the coolly self-confident tycoon, who gives orders as naturally as he breathes, with the shy, stuttering child he once was or the carefree young man-about-town ...” Another passage describes his childhood. “Walter was a shy boy, a major reason being a terrible stutter. Simple words and phrases took him forever to say.”

However, it was during his college years at the University of Pennsylvania, from which he never graduated, that he began a speech therapy program but discontinued it. In his early career, he felt he had to do something about his speech. “Besides working to improve his knowledge of the business, Walter began an agonizing and often frustrating approach to conquering his stutter... But even as he came to dominating his business world, his speaking pattern remained difficult, and it wasn’t unusual for him to pause for painfully long moments before he managed to give an order or discuss the business at hand.

In Legacy: A Biography of Moses and Walter Annenberg, a 1999 work by Christopher Ogden, Annenberg’s sister Evelyn described her brother’s speech, “The stuttering wasn’t just hard for Walter… It was awful.” Ogden wrote, “He did endless exercises reading aloud….Page after page of lists of words, phrases and sentences. Over and over again for what would ultimately be the better part of a century. In his eighties and nineties, Walter continued to do his speech exercises daily, a sign that he was never ‘cured’ and of his determination and discipline. Every day he would have to prove again that he could speak.”

On the day of his 90th birthday, he called Jane Fraser for suggestions on how to cope with his stuttering.

It was while working in the family publishing business that he would return to the therapy program that had been devised by Dr. Edwin Twitmyer of the University of Pennsylvania. In his book Cooney wrote, “The exercises consisted of about twenty minutes a day of recitation, including works such as the Gettysburg Address and Robert Southey’s poem ‘Cataracts of Lodore’, which were therapeutic because of the rich range of vowel sounds. Even to this day, if Annenberg were to discontinue, his speech would rapidly backslide. Thus, to the bewilderment of others on occasion, Annenberg put himself through his lessons wherever he happened to be. While staying at the Beverly Hills Hotel during the Second World War, for instance, his warblings panicked a guest in an adjacent room, who informed the management that a Japanese spy was barking orders at someone next door.”

Of Annenberg’s adulthood, Ogden wrote, “The persistent stuttering was a similar frustration from which he could never escape. “ However, when President Nixon selected Annenberg as Ambassador to Great Britain, there were questions about whether he could handle even the ceremonial diplomatic responsibilities. “Because of his stutter, he was uncomfortable speaking publicly. Before arriving he had written to David Bruce (the previous U.S. Ambassador to the UK), as Bruce noted in his diary, that “he had no desire to make speeches unless it was absolutely necessary.”

Ambassador Annenberg kept a low profile by refusing to speak to the press for his first three months. Ogden described of Annenberg’s first interview with the British media, the Daily Express, “But he did not explain his lifelong history of stuttering, the speech therapy he had undergone for years and that he always chose every word with particular care. To minimize his stammer, he tried to frame entire sentences before opening his mouth. The result was often circumlocution as phrases poured from his mouth complete with whereases and heretofores. In the presence of the Queen, he had been determined not to stumble over his words.” Of course, people who stutter know that Queen Elizabeth was most compassionate with Annenberg’s stuttering because of her late father King George VI’s history with the speech disorder.

Henry Luce and Walter Annenberg did amazing things in their storied careers and lives. The fact that both of them were involved in speech therapies and struggled with stuttering throughout their entire lives is a compelling testament for perseverance in one’s chosen profession. These two famous Americans never once let stuttering hold them back from achieving their phenomenal success.

From the 2016 Summer Newsletter

Podcast

Podcast Sign Up

Sign Up Virtual Learning

Virtual Learning Online CEUs

Online CEUs Streaming Video Library

Streaming Video Library