The fascinating career of Edward Hoagland, novelist and nature writer was featured in the April 9th, 2012, Wall Street Journal article “Tracking the naturalist.” The article shed light on Hoagland’s amazing exploits that fueled his conservation writing for almost sixty years. The 79 year-old writer said, “Our world is being destroyed in a quiet holocaust. It’s up to us to say what we have to say while we can still do so.”

The fascinating career of Edward Hoagland, novelist and nature writer was featured in the April 9th, 2012, Wall Street Journal article “Tracking the naturalist.” The article shed light on Hoagland’s amazing exploits that fueled his conservation writing for almost sixty years. The 79 year-old writer said, “Our world is being destroyed in a quiet holocaust. It’s up to us to say what we have to say while we can still do so.”Born in New York City in 1932, Hoagland’s family moved to rural Connecticut, which fostered his interest in nature. “He also suffered from a profound stutter that, while he wasn’t without friends, made nature, where quiet attentiveness rather than chatter is the coin of the realm, a natural fit.”

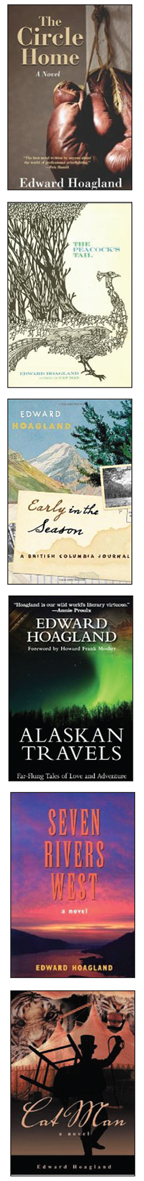

He is best known as a nature and travel writer, but has also penned five novels in addition to his 10 books of essays and three travel books. His first novel Cat Man was inspired by his experience tending big cats with the Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus during vacations while an undergraduate student at Harvard. Some of his books of essays include The Courage of the Turtles, The Tugman’s Passage, and Tigers & Ice. Two of his travel books are Notes from the Century Before: A Journal from British Columbia and African Calliope: A Journey to the Sudan.

His 2001 memoir Compass Points: How I Lived reflects how stuttering affected him. He wrote he was always painfully embarrassed when visiting relatives in Pennsylvania as a child because an older cousin would use public occasions to try to cure his stuttering through her own “know-it-all” methods. Of his college years at Harvard, he penned, “Mute because of a bad stutter, I’d wandered Boston’s night neighborhoods with hungry yearning throughout my college years.”

However, Hoagland also described how his love for nature and animals gave him a much needed solitary world where he was not held back from expressing himself. He wrote, “…spurred in particular with my fascination with animals. At home in Connecticut I’d kept dogs, cats, turtles, snakes, alligators, pigeons, possums, goats…” In addition, the Dictionary of Literary Biography states the following, “Hoagland’s love of solitude and silent observation of wildlife rather than social conversation may have resulted from a severe stammer that still persists. The stammer has, according to Hoagland himself, influenced how he writes: ‘Words are spoken at considerable cost to me, so a great value is placed on each one. That has had some effect on me as a writer. As a child, since I couldn’t talk to people, I became close to animals. I became an observer, and in all my books, even the novels, witnessing things is what counts.’ His reluctance to speak may account for his desire to write – and be read – and for the sensitive visual, tactile, and olfactory images in his writings.”

Furthermore, he writes in his memoir that he made the switch from writing fiction to essays because of “the painful fact that I stuttered so badly that writing essays was my best chance to talk.”

The subject of his stuttering appears in some of his essays. An obvious example is his essay On Stuttering he states flaws like stuttering should be cherished and embraced despite the many challenges and pains they may cause. Hoagland believes that striving to accept yourself adds to your character and sense of self, and not letting your flaws overcome you or define you. He describes the most memorable times in his life when it was frightening to use or not be able to use his voice. A most chilling example occurred when he was in the woods and a hunter mistook him for a deer and was prepared to shoot; Hoagland had to speak up and get the words out to save his own life.

Hoagland was also legally blind. In 1991 he underwent a very risky, yet successful, operation to restore his sight. Being deprived of his eyesight and the freedom to go on walks, he was robbed of his keen sense of observation which fueled his life as a writer. Unexpectedly during this time, the author inexplicably stopped stuttering and was fluent. He commented, “It just seemed that I had to talk since I could no longer see. So I just started talking.”

People who stutter are proud that this premiere nature writer not only identifies with their stutter but also that stuttering fostered his career as a nature writer.

From the Fall 2012 Newsletter

Podcast

Podcast Sign Up

Sign Up Virtual Learning

Virtual Learning Online CEUs

Online CEUs Streaming Video Library

Streaming Video Library