Our colleague, Glyndon Riley, passed away on September 2, 2014. He, and wife Jeanna — may she continue to be with us for many years to come — jointly demonstrated a life-long devotion to advancing our knowledge of stuttering, improving the communication and quality of life of children and adults who stutter, and made outstanding contributions to the enhancement of our discipline. It has been an unusually well-rounded contribution.

Our colleague, Glyndon Riley, passed away on September 2, 2014. He, and wife Jeanna — may she continue to be with us for many years to come — jointly demonstrated a life-long devotion to advancing our knowledge of stuttering, improving the communication and quality of life of children and adults who stutter, and made outstanding contributions to the enhancement of our discipline. It has been an unusually well-rounded contribution.

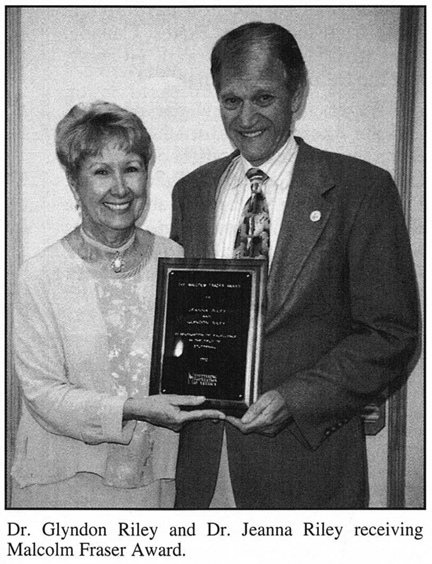

Glyndon Riley received his Ph.D. degree from Florida State University, was employed as a school teacher, a professor of communication disorders at California State University at Fullerton, and a speech-language clinician in several settings. He played an active role in many community projects and agencies devoted to the service of handicapped children where much emphasis of his work was directed toward helping those who stuttered. As a Fellow of ASHA and member of the International Fluency Association, he served on numerous committees of these organizations and was also the recipient (jointly with Jeanna) of the Malcolm Fraser Award for excellence in the field of stuttering. Glyn was among the few who excelled both as a master clinician and an accomplished investigator, striving to advance scientific knowledge about stuttering. He realized the aspiration of many to become a scientist-practitioner, that is, to employ the scientific method in one’s clinical practice and ensure that one’s clinical work has scientific underpinnings.

An historic perspective on the Rileys’ work reveals the development of a theoretical framework that views stuttering as a heterogeneous disorder with multiple etiologies. This view emerged and grew out of research that substantiated evidence of variability among children and adults who stuttered. Theirs was one of the first serious attempts to identify subgroups of young children who stutter in order to facilitate early prediction of the risk for chronic stuttering. These research findings served as the basis for the well-known Stuttering Prediction Instrument. The Rileys’ efforts provided an important impetus to current extensive research in this area by other investigators. They also developed a Component Model to describe a child who is vulnerable to developing chronic stuttering. This model was, in fact, an early version of the capacities and demands concept. Attending, Language Formulation, and Oral Motor Coordination were placed at the capacity end of the scale with Self-demand and Audience-demand at the demand end.

A second Riley contribution was in quantifying stuttering, one of the major issues still confronting those who work with the disorder. Once again, the Rileys’ research endeavor was clearly oriented toward yielding a practical tool. For many years, clinicians and researchers alike lacked a proper global measure of stuttering that would enable them to capture in a single score many of the features that contribute to the disorder. The Stuttering Severity Instrument (SSI) was a major development in the field, impacting both the research and clinical domains. It has been widely employed in many studies conducted by various investigators, allowing them to be more accurate in selecting subject samples and make much needed comparisons among different groups. It left its greatest mark, however, on routine clinical procedures. Scores on the SSI have probably been the most commonly used in diagnostic and progress reports. Furthermore, care has been taken to improve and update this tool several times.

A third major research-clinical contribution by Glyndon and Jeanna Riley was their research-based therapy program. As their work on differentiation among children who stutter progressed, linguistic and oral motor abilities (e.g., syllable production) emerged as significant variables, consistent with their multiple etiologies, multiple risks perspectives. As was the case with the Stuttering Prediction Instrument and the Stuttering Severity Instrument, the Rileys research in this area culminated in a meaningful clinical application: a therapeutic approach known as the Speech Motor Training Program. In clinical trials, they improved voicing accuracy, coarticulation, and sequencing, which were accompanied by reduced stuttering as well as a more appropriate speaking rate.

Another significant contribution identified with the Rileys is their research on clinical efficacy. With the support of an NIH grant, a major four-year study (with Janis Ingham) of two treatment methods, Speech Motor Training and Extended Length of Utterance, were tested in children ages three through nine. At the time, this was the largest systematic, controlled study of clinical efficacy in childhood stuttering ever conducted. This project not only served as an impetus for much needed research in this area, but, typical to the Riley’s work, it yielded information pertinent to clinicians’ immediate needs. The research showed that both methods can effectively and substantially, though to a different degree, decrease stuttering.

Fifth, in the mid1990s, Glyndon became involved in more basic research exploring brain activation patterns of people who stutter as a member of a team at the Brain Imaging Center at the University of California at Irvine. The early initial published findings of that work (with Wu et al.) showed aberrant patterns of cerebral activation, including increased activation of the supplementary motor area. This research was then expanded by others, such as the Fox, Ingham et al. team. Finally, and so characteristically, in most recent years Glyndon was on the research team (Maguire et al.) that conducted large scale clinical studies of a new drug, Pagoclone, as applied to the treatment of stuttering.

Sixth, the contributions of the Rileys have extended well beyond the research laboratory and speech clinic into the realms of educating speech-language pathologists who are qualified to provide service to the speech-language handicapped, including those who stutter. During 40 years in university settings, Glyndon taught many courses on stuttering and mentored a large number of graduate students preparing to become speech/language clinicians. In addition to their own intensive clinical work, the Rileys maintained a large clinical staff in their center for stuttering and made their resources available to train clinicians in their clinical fellowship year, continually upholding the high standards that they set for themselves. Their on-site supervision helped clinicians adapt to the special problems that arise with children of bilingual and multicultural backgrounds.

Within this rich mix of activities, yet a seventh contribution should be recognized: public service for which the Rileys received the Outstanding Achievement Award from the California Speech-Language-Hearing Association (CSHA). Of the many services, only a few are mentioned here. One dream realized was the establishment of a center dedicated to serving children who stutter. It has been committed to the prevention of stuttering as well providing diagnosis and treatment services, especially to those lacking financial means. Its annual Fluency Conference has reached out to about 125 clinicians each year for 16 years, positively effecting thousands of children and their families as clinicians are more educated about stuttering. Glyndon was also deeply involved with educating the medical community about stuttering while, in an altogether different vein, he was active in community disaster preparation.

Most admirable about Glyndon and Jeanna has been their unmistaken optimism, friendliness, and true collegiality. Their demonstrable appreciation for different views has provided us with a model of positive attitudes toward other professionals inside as well as outside the field. By advocating and practicing openness in their writings, presentations, and daily personal and professional lives, they have elevated the professional dialogue concerning stuttering. Glyndon was a true gentleman; may his memory be for a blessing, and may Jeanna be blessed for long life.

Ehud Yairi

Posted Sept. 12, 2014

Podcast

Podcast Sign Up

Sign Up Virtual Learning

Virtual Learning Online CEUs

Online CEUs Streaming Video Library

Streaming Video Library