An excerpt of Chapter 4 by Dean E. Williams, Ph.D., from the book Stuttering and Your Child: Questions and Answers

An excerpt of Chapter 4 by Dean E. Williams, Ph.D., from the book Stuttering and Your Child: Questions and AnswersHow can I talk to my child about talking?

It helps when discussing stuttering with a child to explain it by using analogies taken from common experiences in his every day life. This approach enables the child to view stuttering not as something mysterious and scary but as something understandable and solvable. It also provides a common platform from which you and your child can understand what each is talking about. Such mutual understanding helps to get the child on a positive course for coping with his speech problem.

Your child is learning new things every day. We know, but sometimes forget, that making mistakes is an essential part of learning. He can be helped to understand that he made mistakes when he learned to dress himself, when he learned to eat with a spoon, when he learned his A B C’s, or to count, etc. But the mistakes were okay. They were a normal part of learning.

How can I reassure my child it’s okay to make mistakes?

Learning to talk is a big job for a little person. It’s very important with young children to view the stuttering as “making mistakes.” He is repeating sounds and words. That’s all right. Everyone makes mistakes as they learn to talk. Some make more than others—just as some children make more mistakes than others as they learn to count, or, to read, or to catch a ball, and so forth. (Examples used should correspond to your child’s own interests.) Your child is probably making more mistakes than many children when he talks, but probably not as many as some of his friends as he learns other things. It helps to have this pointed out to him. His speech will undoubtedly develop all right. In the meantime, it’s helpful to reassure your child that it’s okay to make mistakes—that it is much more important to you that he talks and has fun talking. If he does this, then it will be easy for you to learn the things he thinks about, the way he feels, and the things he likes and doesn’t like. Assure him that these are the important things about talking—not whether he makes mistakes as he learns how to talk.

What if my child is tensing and struggling as well as repeating sounds?

If your child is not only repeating sounds but also is tensing and struggling, you can follow the same kind of explanation as outlined above. However, there will be a need to add to the examples.

Let us say as an illustration that a child is learning to catch a ball. He’s dropping the ball quite a bit. He doesn’t like doing this, so he begins to tense up and “pounce” at the ball. He begins to drop it more often. He is now trying hard “not to drop it.” The same thing occurs when one begins to learn to ride a bicycle. Often the child will tense up to try “not to fall off.” He will fall off more often. In a sense these children are “fighting the making of mistakes.”

The same thing can happen if a child begins to believe he should not make mistakes while talking. In an effort to “not” make them, he physically tenses and struggles. This only makes talking more difficult. He can be helped to see that it is more beneficial to “go ahead and talk and stutter easily.” This makes it easier for him to say what he wants to say.

What do I tell his brothers and his sisters about stuttering and about what they can do to help?

You can explain stuttering to his brothers and sisters in much the same way as you explain it to your child. He can be present or not when you explain it to them. There is nothing secretive about making mistakes and even fighting them—we all can give examples—even his brothers and sisters. Explained in this way, it makes it easier for them to understand what they can do to be helpful. After all, if they were having difficulty learning an activity, they would want others: (1) to give them time to work through their mistakes; (2) to wait calmly and not interrupt them; and (3) not to jump in and do it for them. The same is true for a child who is stuttering (reacting to disruptions in his speech).

As a way to help, set up talking rules in your home. The talking rules apply to your child who stutters as well as to his brothers and sisters.

1) We don’t interrupt each other as we are talking.

2) We take turns talking.

3) We don’t talk for each other. Each does his own talking.

How should teasing be handled?

In addition to talking rules, I suggest that you establish a position about teasing. If discussions have been open about your child’s stuttering problem, there should be a minimum of teasing. However, if teasing occurs by a brother or sister, it is easy to point out to them that if they worked hard on a math paper, for example, and then made many mistakes, they feel bad. They would then feel even worse if anyone teased them at that time. The same is true when they tease anyone else. You can set up a rule that in your family, one doesn’t tease another about the way he or she does things. To do so only makes one feel sad. Teasing doesn’t help one learn—and we are a family, and we are all trying to help each other.

What do I say to his friends?

Essentially, you can talk to them the same way I suggested you talk to his brothers and sisters. It is not unusual for a friend of your child to turn to you and ask “How come he talks that way?” or, “Why does he stutter?” Again, it is important when you answer your child’s friend in an open, matter-of-fact way. Your child will likely be present. Your answer to the friend should be similar to the explanation that you gave to your child and to his brothers and sisters. Presenting similar explanations about stuttering to your child’s friends enables you to handle any teasing by friends in the same way explained previously for brothers and sisters.

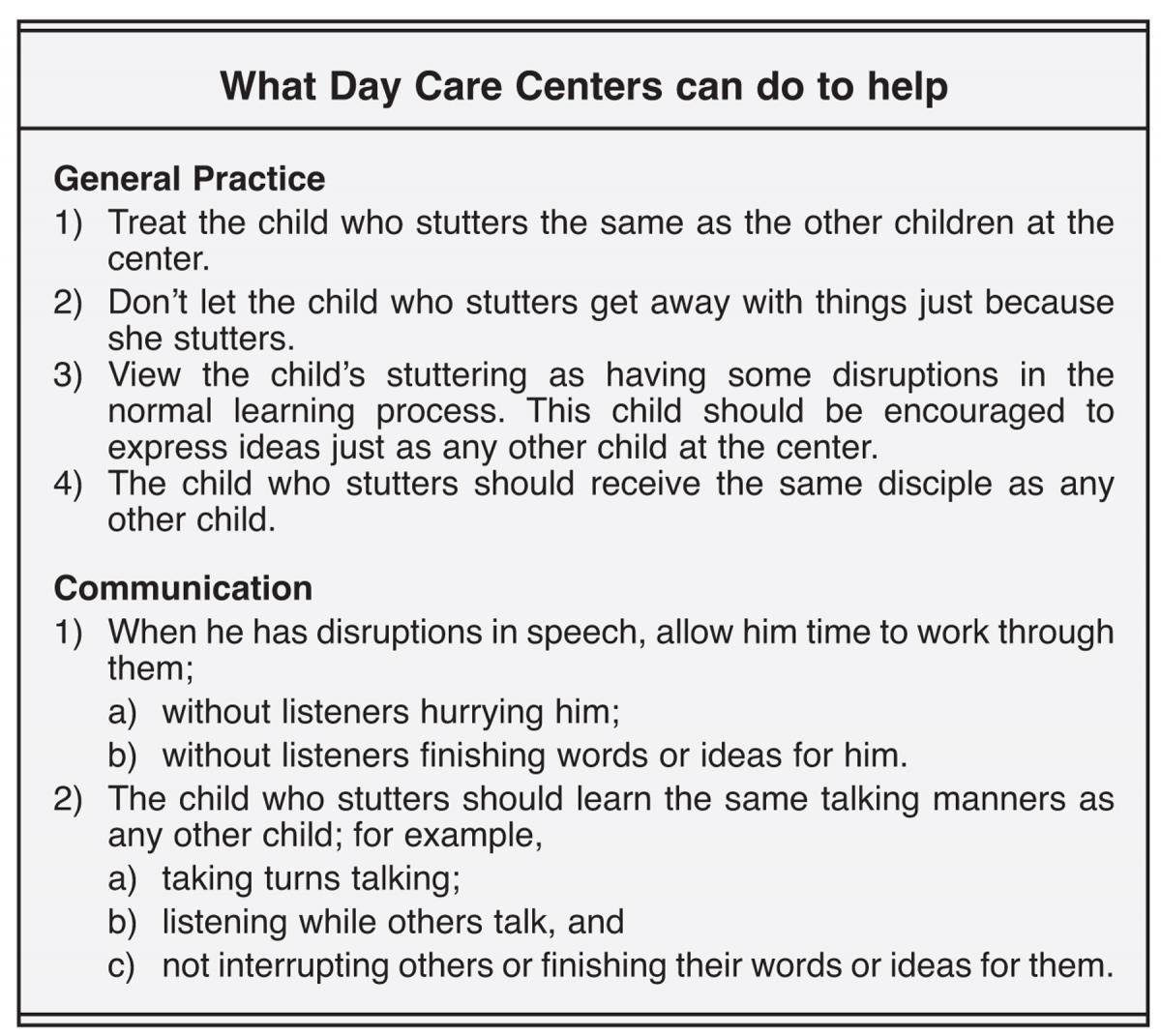

What do I say to the sitter and to the people at the day-care center?

What do I say to the sitter and to the people at the day-care center?Explain to adults who take care of your child, in a matter-of-fact way, that he is stuttering some during this phase of learning to talk. Make it clear to them that you want him to talk to them and you want them to talk to him. If you can help them view the stuttering as the making of mistakes, then it will be easier for them to see that he should be encouraged to express ideas just as any other child.

You also can help them understand that when disruptions occur, the child should be given the time he or she needs to work through them. Listeners should try not to hurry him or finish words or ideas for him. At the same time, he should receive the same discipline practices as any other child. Also, he can be helped to learn the same talking manners as any other child. He should learn to “take turns” in talking, and he should not interrupt, talk for, or finish words for anyone else—any more than they for him.

When his grandparents or his aunts and uncles ask, what should I say about his stuttering?

Try to adopt the same basic philosophy with close relatives we discussed above under ways to talk to your own child and to his brothers and sisters about stuttering. This enables all close family members to see the problem in the same way. It provides a common-sense approach that is readily understandable by all. This approach encourages all “family” to be consistent in the ways they react to the act of stuttering and to the child who is doing it.

What should I do if my child stutters in public and if a stranger comments about it?

At times this may be difficult, but remember when a child stutters, he is talking—and when he is talking, he is trying—although clumsily at times—to send you a message. Therefore, attend to, and work to interpret the child’s message. Don’t get sidetracked by the static, the hesitations, that may be accompanying the child’s message.

If he stutters in public, or anywhere else for that matter, pay attention to and respond to what he is telling you rather than to how he is telling it.

What do I say to him when he is teased by his friends or his classmates?

Teasing is a common problem that most children have to deal with as a part of growing up. If they are not teased about their speech, they likely will be teased about something else—for example, the color of their hair, the glasses they wear or even the way they eat a hamburger. Undoubtedly, your child (like all children) will experience his share of teasing. In any event, he needs to be helped to understand about teasing generally. Then, it will be easier for him to figure out how to handle it.

You can help by listening and talking to him about his feelings about being teased. Also, you can discuss together the things one can do when teased. You can even talk about the way you felt and the things you did when you were teased as a child. Another thing you can do is to help him focus his attention on other things. For example, go for an ice cream cone, suggest he call a close friend, discuss plans for an upcoming event, and so forth.

As I talk to children about the teasing they do, they explain to me that they are not trying to be mean or to hurt one’s feelings. They are just “kidding around.” They say that they only “kid around” with their friends. They don’t kid around with those they don’t like or don’t know. In my experience, most “teasing” is of this kind. You can work with your child to help him to decide the best way to handle it. If there is one child or a small group who tease to be cruel, then often it is best to discuss with the teacher, and, if necessary, the school counselor the best ways to handle it.

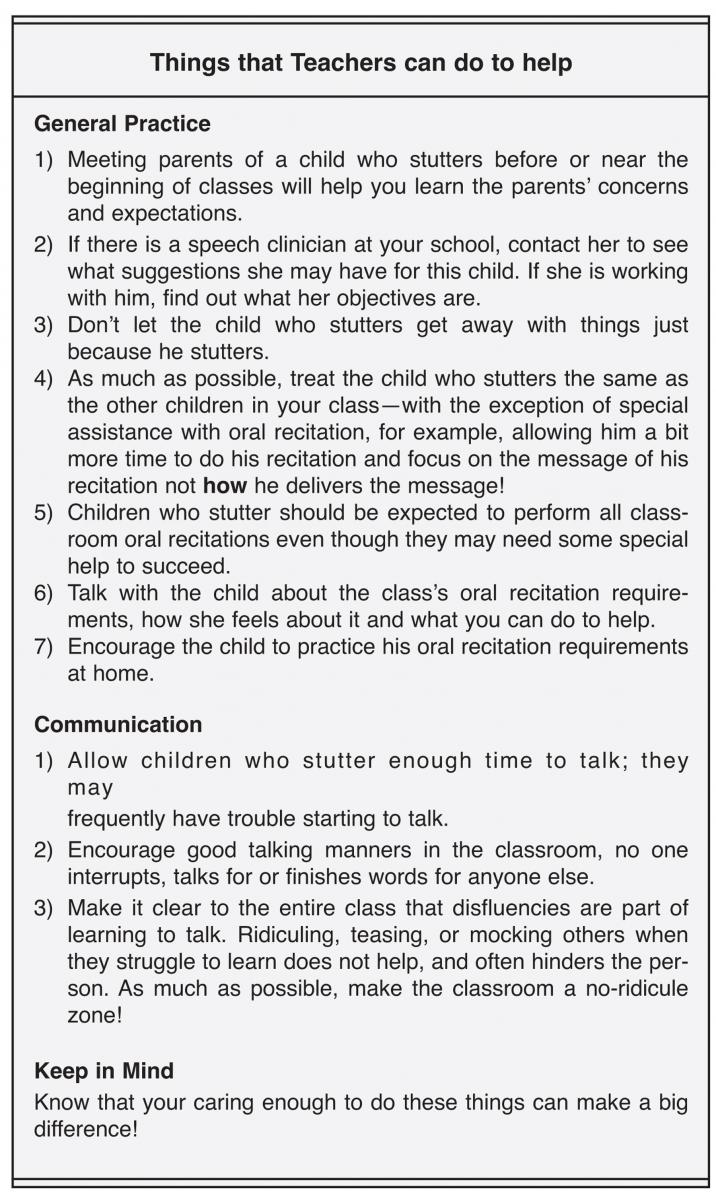

What do I say to his teachers?

It is a good idea to make an appointment to meet your child’s classroom teacher before classes begin. Teachers welcome the chance to discuss stuttering openly with parents. It will help the teacher to decide the most reasonable ways to handle your child’s speech in the classroom if she learns how you have been handling it at home. She can appreciate the fact that you have talked to your child about hesitations, repetitions and other disruptions in speech as “mistakes we make while learning to talk.” Also, that the related physical tensing and struggling (if present) are efforts to fight or hide the mistakes. After all, the teacher’s job is to help children learn. Teachers know how upset some children become when they don’t do things “right.”

It is a good idea to make an appointment to meet your child’s classroom teacher before classes begin. Teachers welcome the chance to discuss stuttering openly with parents. It will help the teacher to decide the most reasonable ways to handle your child’s speech in the classroom if she learns how you have been handling it at home. She can appreciate the fact that you have talked to your child about hesitations, repetitions and other disruptions in speech as “mistakes we make while learning to talk.” Also, that the related physical tensing and struggling (if present) are efforts to fight or hide the mistakes. After all, the teacher’s job is to help children learn. Teachers know how upset some children become when they don’t do things “right.”The teacher will want to know that at home you encourage your child to say what he wants to say even though he has some disruptions while saying it. You will want to tell the teacher that you listen to what he says, not react to how he says it. You compliment him—not for speaking fluently, but for an interesting observation of good talking manners in the home. No one interrupts, talks for, or finishes words for anyone else.

You will want to learn from the teacher the kinds of oral recitation (oral reading, short answers, oral reports) the children perform. It will be helpful if you then talk about this with your child so he knows what to expect. Suggest to the teacher that she do the same thing. You both can learn the way he feels about it—the parts that don’t worry him and the parts that do. Then you and the teacher can discuss the best ways to help him meet oral recitations constructively.

Are there classroom activities that can help children who stutter?

There are simple, common sense adjustments that teachers can make to routine classroom activities that have been found to be helpful to other children. These include:

Oral Presentations in School

(a) If the child is fearful of reciting orally, his reading assignments can be sent home. You can have him practice reading them alone to you. This enables him to gain confidence of knowing all of the words, and it gives him the experience of hearing his voice as he reads.

Answering Questions in School

(b) If he is afraid of being asked questions to be answered aloud, you can pretend to be the teacher and ask him to answer questions aloud. This enables him to practice taking the time to answer, to revise an answer, and generally to “think on his feet” out loud.

Telling Stories in School

(c) If he is afraid of activities involving telling a story or giving an oral report, he can prepare it and present it to you—and perhaps to other members of the family.

If the teacher knows the things you are doing at home, she can plan her activities with the child accordingly. As much as possible, the teacher should ask the child to recite just as she does any other child in the classroom.

If speech therapy is recommended, indicate to the speech clinician and to the teacher that you will cooperate in every way possible.

Podcast

Podcast Sign Up

Sign Up Virtual Learning

Virtual Learning Online CEUs

Online CEUs Streaming Video Library

Streaming Video Library