Childhood Stuttering

A new look at how language, motor, and emotion factors may influence early childhood stuttering

By Hayley S. Arnold, Ph.D.

Purdue University

Fall 2009

As a postdoctoral researcher in the area of stuttering at Purdue University, I am studying how language, motor, and emotion factors may influence stuttering in young children.

As a postdoctoral researcher in the area of stuttering at Purdue University, I am studying how language, motor, and emotion factors may influence stuttering in young children.

One way I’ve explored these factors is with electroencephalography (i.e., EEG, electrical signals from the brain) in preschool-aged children who stutter and their peers who don’t stutter.

During my previous doctoral work with Edward Conture at Vanderbilt University, I measured emotions using EEG and the behaviors produced by nine children who stutter and nine children who don’t stutter. The EEG measures of emotion did not distinguish children who stutter from those who don’t stutter. However when I analyzed behaviors, the children who stutter, compared to their peers who did not stutter, were less adept at emotion regulation.

The study had children listen to several conversations in which adults were happy, angry, and neutral in their emotions.

I found that the children who did not stutter responded with significantly more frequent self soothing, problem solving, and other regulatory behaviors immediately after hearing the happy and angry conversations compared to the neutral one.

The children who stutter used about the same frequency of regulatory behaviors across the happy, angry, and neutral conversations.

I also found that the children who stutter using fewer emotion regulation strategies also stuttered more. In other words, it appears that use of regulatory behaviors is related to stuttering; however, we do not know if the stuttering decreases the occurrence of the regulatory behaviors or if less regulatory behavior results in more stuttering. Further research is needed to answer this question.

More recently, I studied electrical brain responses (i.e., event-related potentials) when 4 and 5 year old children who stutter listened to sentences while they watched a cartoon. These 26 children, thirteen who stutter and thirteen who don’t, were in their first year of a longitudinal project directed by Anne Smith and Christine Weber-Fox at Purdue.

When we analyzed their brain responses, we saw subtle, but statistically significant, differences for the children who stutter compared to their peers who do not stutter. The differences in brain activity were more pronounced when the children heard words that were out of order in a sentence (“He wanted this that ball”) rather than the meaning of words (“He stood on the one music”). This study is helping us to understand that the brain activity for language may differ for some children who stutter when they are simply listening to speech without speaking themselves.

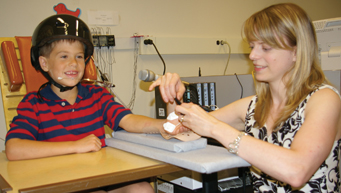

I’ve also started studying the body’s response to emotions (i.e., autonomic arousal) by measuring changes in the skin related to sweat gland activity and blood flow. This study includes school-age children who stutter and their peers who do not during speech and non-speech tasks.

Because the recordings we use are “kid friendly,” the children often talk about how much fun they had and even ask when they can return! I hope that these and other studies will help us better understand stuttering and eventually lead to therapy that helps prevent chronic stuttering.

If you live in Indiana and would like your child who stutters to participate in our studies, e-mail harnold@purdue.edu [1].