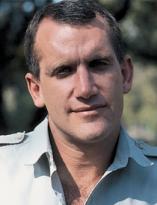

Alan Rabinowitz

Alan Rabinowitz, Ph.D., who passed away in 2018, was an explorer, wildlife conservationist, and author. He established the Hukawng Valley Tiger Reserve in northern Myanmar, which is about the size of the state of Vermont.

His love for animals began when he was very young.

"Animals were the only things I could talk to as a child," he explained during a Stuttering Foundation workshop. "Animals listened and let me pour my heart out. At some point in my youth I clearly remember realizing that animals were like me, even the most powerful ones I'd read about or seen on television - they had no voice, they were often misunderstood, and they wanted nothing more than to live their life as best they could apart from the world of people."

Here's Alan in his own words...

“For the past 25 years of my life, I have lived in and explored some of the most remote places on earth. I have lived for days in caves chasing bats, I have captured and tracked bears, jaguars, leopards, tigers, and rhinos. I have discovered new animal species in northern Burma and in the cloud forests of the Annamite Mountains. I have documented lost cultures such as the Taron, the world’s only Mongoloid pygmies. I have been called the “Indiana Jones of Wildlife” by the New York Times and given lectures all over the world to thousands of people. Yet not a year has passed, not a country traveled in, when I have not felt again the little stuttering, insecure boy inside who’d come home from school and hide in a corner of his closet. That boy is never far from the surface.

As a youth, my blocks were so severe that my body would twist and spasm in trying to get a word out. So at some point in my early years, I just stopped talking. The greatest of all terrors was to be told that I had to speak in front of the class. I could usually plan some diversion to get out of it, but one day I was taken by surprise. Without thinking, I dropped a pencil on the floor, bent under the desk then stabbed the pencil through my hand so that I had to be taken to the hospital. Now I wouldn’t have to read in front of the class. The pain in my hand was nothing compared to the anticipated pain of pity and ridicule.

The event that haunts me most in my life happened when I was about 15 years old. I was at the store picking up groceries. When my turn in line came I could not say my name. One person waiting told another that I was probably retarded, so I exaggerated my blocks and took on the role of a retarded child. It was easier to be what people thought me to be, than to be who I knew I was.

This was a turning point in my young life, for I swore that I would never deny myself again, and that I would strive not to be just like other people but to be far better than everyone else.

One of the most common questions I am asked is how I came to love animals so much. People expect many answers but never what I give them. Animals were the only things I could talk to fluently as a child. Animals listened and let me pour my heart out. Animals were like me, even the most powerful ones had no voice.

My parents never knew quite what to do with me. We never talked about stuttering, for they felt that to discuss it would give me more pain. Yet the silence was a much greater pain. When they finally faced the fact that everything was not okay with me we tried drugs, hypnotherapy, and a host of speech specialists who told me that I had to accept who I was, stuttering and all, and move on. The therapists were good people, trying to do good things. The problem was that they just didn’t know what to do.

Finally one day we learned of Hal Starbuck’s clinic in Geneseo, NY. I was 18 years old, never had a date with a girl, never went to a school dance, and never knew what it was like to speak a complete sentence fluently. Then my life turned around.

Starbuck’s clinic made me face the fact that I was a stutterer. The difference was he offered to me the tools to be a fluent stutterer—tools that were by no means easy to master but were within reach of anyone who wanted them badly enough. I was no longer helpless and foundering. I could be in control if I wanted to be.

But learning to speak fluently, while feeling wonderful, didn’t heal the scar tissue that had accrued from all those years of suffering. I ran as fast and as far as I could—combining a need to pay back the debt I owed to animals with the desire to test myself, physically and mentally, to be lost in the wild, the dark closets of the world.

I had to purge the feelings of shame, fear, and inadequacy that so controlled my life for so long. I was a little stuttering boy, now a man, who simply ran to the farthest reaches of the earth to try to feel whole. I just wanted to feel whole.

Over the years I did reach that goal and it became harder for me to run away as the wildlife I had come to love was being lost around me, despite my own and others’ efforts. I had to be their voice.

Speaking out about my stuttering is another chapter in my life. I don’t want other young people to go through what I went through. The speech community has clearly gone through radical changes since I was a boy, and those who stutter now have many places to turn for help. But the general public’s understanding of stuttering is not what it should be. And I have been surprised to learn that many speech language pathologists still say the same things to young people that they said to me. Some still feel uncomfortable and others are frustrated when they don’t get the kind of response they want or expect from someone who stutters.

If I could be with you today, I would tell you that everyone who stutters can be a fluent speaker, if they choose.

I believe that stuttering is a gift granted to certain people, a key that opens up parts of the human psyche that would not be opened otherwise. I also think that those who work with stutterers can come away better people themselves for it, if they open their minds and hearts to what they are experiencing.

But nice words and thoughts do not negate the handicap that stuttering can create in young and old alike. That handicap can be fixed. Maybe not quickly. Maybe not easily. The key is not giving up—for both the clinician and the client. No one should have to suffer through life because they stutter."